Event

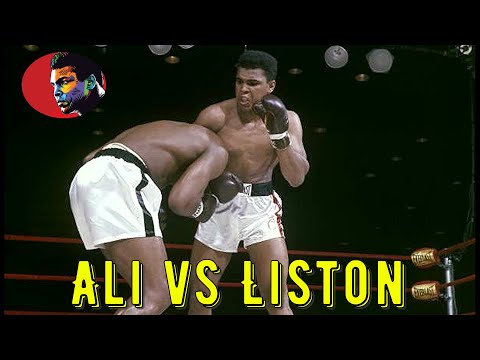

Cassius Clay vs Sonny Liston

Date

Tue 25th February 1964 (UTC)

Tue 25th February 1964 (Local)

Timestamp

1964-02-25T00:00:00

Time

00:00:00 UTC

00:00:00 UTC

Timezones

24-11-23 16:00 (PST Los Angeles)

24-11-23 16:00 (PST Los Angeles)

24-11-23 18:00 (CST Chicago)

24-11-23 18:00 (CST Chicago)

24-11-23 19:00 (EST New York)

24-11-23 19:00 (EST New York)

24-11-24 00:00 (GMT London)

24-11-24 00:00 (GMT London)

24-11-24 01:00 (CET Paris)

24-11-24 01:00 (CET Paris)

24-11-24 04:00 (GST Dubai)

24-11-24 04:00 (GST Dubai)

24-11-24 05:30 (IST Kolkata)

24-11-24 05:30 (IST Kolkata)

24-11-24 09:00 (JST Tokyo)

24-11-24 09:00 (JST Tokyo)

24-11-24 11:00 (AEDT Sydney)

24-11-24 11:00 (AEDT Sydney)

Poster

Your Rating (Click a star below)

Cassius Clay vs Sonny Liston

Date

Tue 25th February 1964 (UTC)

Tue 25th February 1964 (Local)

Timestamp

1964-02-25T00:00:00

Time

Timezones

Poster

Your Rating (Click a star below)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Total Rating![]() (0 users)

(0 users)

Thumb

Square Poster

League

Boxing

Season

1964

Round

0

Status

Location Convention Center

Convention Center

Video Highlights

Description

Background

Liston was the World Heavyweight Champion at the time of the first Liston–Clay fight in Miami Beach on February 25, 1964, having demolished former champion Floyd Patterson by a first-round knockout in September 1962. Ten months later, Liston and Patterson met again with the same result—Patterson was knocked out in the first round.

At the time of the fight, Liston was generally considered the most intimidating fighter in the world, and among the best heavyweight boxers of all time. With the Patterson victory, Liston had defeated eight of the top 10 ranked contenders at heavyweight, seven of which by knockout. Many were reluctant to meet him in the ring. Henry Cooper, the British champion, said he would be interested in a title fight if Clay won, but he was not going to get in the ring with Liston. Cooper's manager, Jim Wicks, said, "We don't even want to meet Liston walking down the same street."

Boxing promoter Harold Conrad said, "People talked about Tyson before he got beat, but Liston was more ferocious, more indestructible. ... When Sonny gave you the evil eye—I don't care who you were—you shrunk to two feet tall." Tex Maule wrote in Sports Illustrated: "Liston's arms are massively muscled, the left jab is more than a jab. It hits with true shock power. It never occurred to Liston that he might lose a fight." Johnny Tocco, a trainer who worked with George Foreman and Mike Tyson as well as Liston, said Liston was the hardest hitter of the three. Several boxing writers actually thought Liston could be damaging to the sport because he could not be beaten. Liston's ominous, glowering demeanor was so central to his image that Esquire magazine caused a controversy by posing him in a Santa Claus hat for its December 1963 cover.

Liston learned to box in the Missouri State Penitentiary while serving time for armed robbery. Later, he was re-incarcerated for assaulting a police officer. For much of his career, his contract was majority owned by Frankie Carbo, a one-time mob hit man and senior member of the Lucchese crime family, who ran boxing interests for the Mafia. The mob was deeply entrenched in boxing at every level at the time, and Liston was never able to escape being labeled as the personification of everything that was unseemly and criminal in the sport, despite the fact that his criminality had been in the past. He distrusted boxing writers, and they paid him back, often depicting him as little more than an ignorant thug and a bully. He was typically described in thinly veiled racist terms—a "gorilla" and "hands like big bananas". Author James Baldwin understood Liston perhaps better than anyone in the press and sympathized with him and liked him, unlike boxing writers. He said, "Liston was the big Negro in every white man's hallway." He was a man who, according to Ali biographer David Remnick, "had never gotten a break and was never going to give one".

On the other hand, Clay was a glib, fast-talking 22-year-old challenger who enjoyed the spotlight. Known as "The Louisville Lip", he had won the light heavyweight gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Italy. He had great hand and foot speed and lightning fast reflexes, not to mention a limitless supply of braggadocio. However, Clay had been knocked down by journeyman Sonny Banks early in his career, and, in his previous two fights, had eked out a controversial decision against Doug Jones and—more seriously—was knocked down by a left hook at the end of round four against the cut-prone converted southpaw Henry Cooper. Clay was clearly "out on his feet" in his corner between rounds, and his trainer, Angelo Dundee, stalled for time to allow Clay to recover. Although Clay rallied to win the fight in the next round, it seemed clear to many that he would be no match against the daunting Liston, who seemed a more complete boxer in every way than Cooper.

The brash Clay was equally disliked by reporters and his chances were widely dismissed. Lester Bromberg's forecast in the New York World-Telegram was typical, predicting, "It will last longer than the Patterson fight—almost the entire first round." The Los Angeles Times' Jim Murray observed, "The only thing at which Clay can beat Liston is reading the dictionary," adding that the face-off between the two unlikeable athletes would be "the most popular fight since Hitler and Stalin—180 million Americans rooting for a double knockout." The New York Times' regular boxing writer Joe Nichols declined to cover the fight, assuming that it would be a mismatch. By fight time, Clay was a seven-to-one betting underdog. Of the 46 sportswriters at ringside, 43 had picked Liston to win by knockout.

Liston, however, brought weaknesses into the Clay fight that were not fully apparent at the time. He claimed to be 32 years old at the time of the bout, but many believed that his true age was closer to 40, perhaps even older. Liston had been suffering from bursitis in his shoulders for close to a year and had been receiving cortisone shots. In training for the Clay fight, he re-injured his left shoulder and was supposedly in pain striking the heavy bag. He secretly resorted to heavy icing and ultrasound therapy after each training session. And, ironically, because of his dominance, Liston had actually logged little ring time in the past three years. Between March 1961 and the Clay fight, Liston had fought three times and won each bout with first-round knockouts—meaning that he had fought a total of just over six minutes during a 35-month stretch.

One of the reasons that Clay's chances were dismissed is that his boxing style seemed ill-suited to the heavyweight division. He was widely viewed as a fast but light puncher lacking the ability to take a punch or to fight inside. The signatures of Clay's style and later greatness—the tendency to keep his hands low and lean away from punches (often leaving his opponent hitting air, off balance, and exposed to counter punches), his constant movement and reluctance to set (making him extremely difficult to hit)—were viewed as fundamental technical flaws that would be quickly exploited by an experienced, hard-hitting heavyweight like Liston. New York Journal-American columnist Jimmy Cannon summarized this view when he wrote: "Clay doesn't fight like the valid heavyweight he is. He seldom sets and misses a lot. In a way, Clay is a freak. He is a bantamweight who weighs more than 200 pounds ."

Liston trained minimally for the bout, convinced that he would dispose of Clay within the first two rounds. He typically ran just one mile a day instead of his usual five, reportedly ate hot dogs and drank beer, and was rumored to have been furnished with prostitutes in training camp.

Pre-fight publicity

The television series I've Got a Secret did multiple segments about the title fight. Panelists Bill Cullen, Henry Morgan and Betsy Palmer predicted that Liston would win in the third, second, and first rounds, respectively. Host Garry Moore was even more pessimistic about Clay's chances, estimating a Liston knockout "in the very early moments of round one," adding, "if I were Cassius, I would catch a cab and leave town." Actor Hal March went a step further, albeit humorously: "I think the fight will end in the dressing room. I think is going to faint before he comes out."

The night before the first fight, on February 24, 1964, the show featured Clay and Liston's sparring partners as guests. Harvey Jones brought with him a lengthy rhyming boast from Cassius Clay:

Clay comes out to meet Liston and Liston starts to retreat,

If Liston goes back an inch farther he'll end up in a ringside seat.

Clay swings with a left, Clay swings with a right,

Just look at young Cassius carry the fight.

Liston keeps backing but there's not enough room,

It's a matter of time until Clay lowers the boom.

Then Clay lands with a right, what a beautiful swing,

And the punch raised the bear clear out of the ring.

Liston still rising and the ref wears a frown,

But he can't start counting until Sonny comes down.

Now Liston disappears from view, the crowd is getting frantic

But our radar stations have picked him up somewhere over the Atlantic.

Who on Earth thought, when they came to the fight,

That they would witness the launching of a human satellite.

Hence the crowd did not dream, when they laid down their money,

That they would see a total eclipse of Sonny.

— Cassius Clay, As read on CBS' I've Got a Secret

Clay also presented that poem on The Jack Paar Show with Liberace giving improvised piano harmony.

Jesse Bowdry brought a much terser written message from Sonny Liston:

Cassius, you're my million dollar baby, so please don't let anything happen to you before tomorrow night.

— Sonny Liston, As read on CBS' I've Got a Secret

The following week, I've Got a Secret brought on two sportswriters whose secret was that they had been the only writers to correctly predict Clay's victory.

Baiting the bear

Clay began taunting and provoking Liston almost immediately after the two agreed to fight. He purchased a bus and had it emblazoned with the words "Liston Must Go In Eight." On the day of the contract signing, he drove it to Liston's home in Denver, waking the champion (with the press in tow) at 3:00 a.m. shouting, "Come on out of there. I'm gonna whip you now." Liston had just moved into a white neighborhood and was furious at the attention this caused. Clay took to driving his entourage in the bus to the site in Surfside, Florida where Liston (nicknamed the "Big Bear") was training, and repeatedly called Liston the "big, ugly bear". Liston grew increasingly irritated as the motor-mouthed Clay continued hurling insults ("After the fight, I'm gonna build myself a pretty home and use him as a bearskin rug. Liston even smells like a bear. I'm gonna give him to the local zoo after I whup him ... if Sonny Liston whups me, I'll kiss his feet in the ring, crawl out of the ring on my knees, tell him he's the greatest, and catch the next jet out of the country."). Clay insisted to a skeptical press that he would knock out Liston in eight rounds (former light heavyweight champion José Torres, in his 1971 biography of Ali, Sting Like a Bee, said that as of 1963, Ali's prophetic poems had correctly predicted the exact round he would stop an opponent 12 times).

Clay's brashness did not endear him to white Americans, and, in fact, even made Liston a more sympathetic character. In The New Republic, the editor Murray Kempton wrote, "Liston used to be a hoodlum; now he is our cop; he was the big Negro we pay to keep sassy Negroes in line."

It has been widely stated that Clay's antics were a deliberate form of psychological warfare designed to unsettle Liston by stoking his anger, encouraging his overconfidence and even fueling uncertainty about Clay's sanity. As Clay himself said, "If Liston wasn't thinking nothing but killing me, he wasn't thinking fighting. You got to think to fight." Former World Heavyweight Champion Joe Louis said, "Liston is an angry man, and he can't afford to be angry fighting Clay." Clay's outbursts also fed Liston's belief that Clay was terrified (something Clay's camp did little to disavow). Clay said later, "I knew that Liston, overconfident that he was, was never going to train to fight more than two rounds. He couldn't see nothing to me at all but mouth." In contrast, Clay prepared hard for the fight, studying films of Liston's prior bouts and even detecting that Liston telegraphed his punches with eye movement.

The Nation of Islam

Several weeks before the fight, the Miami Herald published an article quoting Cassius Clay Sr. as saying that his son had joined the Black Muslims when he was 18. "They have been hammering at him ever since," Clay Sr. said. "He's so confused now that he doesn't even know where he's at." He said his youngest son, Rudy Clay, had also joined. "They ruined my two boys," Clay Sr. said. "Muslims tell my boys to hate white people; to hate women; to hate their mother." Clay Jr. responded by saying, "I don't care what my father said. ... I'm here training for a fight, and that's all I'm going to say."

As the story began to spread, promoters became increasingly uneasy. Bill MacDonald, the main promoter, threatened to cancel the fight unless Clay publicly disavowed the Nation of Islam (NOI). Clay refused. A compromise was reached when Malcolm X, at the time a companion of Clay's as well as a feared and incendiary spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (though Malcolm X had, by that time, been censured by the NOI—banned from speaking to the press and suspended from all official NOI roles and duties—and would soon officially break with the Nation), agreed to keep a low profile, save for the night of the fight when he would rejoin Clay's entourage as spiritual advisor and view the fight from a ringside seat. While Clay would not definitively link himself with the Nation of Islam and its leader, Elijah Muhammad, until the day after the fight—at the annual NOI Savior's Day celebration—his association with the Nation, seen by many as a hate group due in part to its strict anti-integrationist stance, further complicated his relations with the press and the white public, further deprived the fight of the "good guy/bad guy" narrative, and negatively affected the gate. MacDonald would ultimately lose $300,000 on the bout.

According to Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali had converted to Islam and joined the Nation of Islam several years prior to the fight, but had kept his religion and affiliation a secret up until the fight.

The weigh-in

Ali's outbursts reached their peak at the pre-fight weigh-in/physical the morning of the event. Championship bout weigh-ins, before this, had been predictable and boring. Ali entered the room where the weigh-in would be held wearing a denim jacket with the words "Bear Huntin'" on the back and carrying an African walking stick. He began waving the stick, screaming, "I'm the champ! Tell Sonny I'm here. Bring that big ugly bear on." When Liston appeared, Ali went wild. "Someone is going to die at ringside tonight!" he shouted. "You're scared, chump!" He was restrained by members of his entourage. Writer Mort Sharnik thought Ali was having a seizure. Robert Lipsyte, the New York Times writer, likened the scene to a "police action, with an enormous amount of movement and noise exploding in a densely packed room." Amidst the pandemonium, he was fined $2,500 by the commission for his behavior. Ali worked himself into such a frenzy that his heart rate registered 120 beats per minute, more than twice its normal rate, and his blood pressure was 200/100. Dr. Alexander Robbins, the chief physician of the Miami Boxing Commission, determined that he was "emotionally unbalanced, scared to death, and liable to crack up before he enters the ring." He said if Ali's blood pressure didn't return to normal, the fight would be canceled. Many others also took Clay's antics to mean that he was terrified. In fact, a local radio station later reported a rumor that he had been spotted at the airport buying a ticket to leave the country. A second examination conducted an hour later revealed Ali's blood pressure and pulse had returned to normal. It had all been an act. Ali later said, "Liston's not afraid of me, but he's afraid of a nut."

The fight

Liston vs Clay

Date February 25, 1964

Venue Convention Hall

Miami Beach, Florida

Title(s) on the line WBA/WBC Heavyweight Champion

Tale of the tape

Boxer Sonny Liston Cassius Clay

Nickname "Big Bear" "Louisville Lip"

Hometown Sand Slough, Arkansas Louisville, Kentucky

Pre-fight record 35–1 (24 KOs) 19–0 (15 KOs)

Height 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) 6 ft 2+1⁄2 in (1.89 m)

Weight 218 lb (99 kg) 210 lb (95 kg)

Recognition WBA/WBC Heavyweight Champion none

Clay weighed in at 210 lb (95 kg) while Liston was several pounds over his prime fighting weight at 218 lb (99 kg). Many of those watching were surprised during the referee's instructions to see that Clay was considerably taller than Liston. While receiving instructions, Liston glowered at Clay, while Clay stared back and stood on his toes to appear even taller. Clay later said of the moment: "I won't lie, I was scared ... It frightened me, just knowing how hard he hit. But I didn't have no choice but to go out and fight."

At the opening bell, an angry Liston charged Clay, looking to end the fight quickly and decisively. However, Clay's superior speed and movement were immediately evident, as he slipped most of Liston's lunging punches, making the champion look awkward. Clay clearly gained confidence as the round progressed. He hit Liston with a combination that electrified the crowd with about 30 seconds left in the round and began scoring repeatedly with his left jab (the round lasted an extra 8.5 seconds because referee Barney Felix didn't hear the bell). Clay had been hit hard by a right to the stomach, but he said later, "I felt good because I knew I could survive." Milt Bailey, one of Liston's cornermen, recalled, "In the first round Sonny couldn't catch up with Clay, and I thought we might have some trouble." Indeed, it was perhaps the worst round of Liston's career. Between rounds, sitting on his stool, Clay turned to the press contingent at ringside and opened his mouth as if yawning or making a mute roar.

Liston settled down somewhat in round two. At one point, he cornered Clay against the ropes and hit him with a hard left hook. Clay later confessed that he was hurt by the punch, but Liston failed to press his advantage. Two of the official scorers awarded the round to Liston and the other had it even.

In the third round, Clay began to take control of the fight. At about 30 seconds into the round, he hit Liston with several combinations, causing a bruise under Liston's right eye and a cut under his left, which eventually required eight stitches to close. It was the first time in his career that Liston had been cut. At one point in this attack, Liston was rocked as he was driven to the ropes. Les Keiter, broadcasting at ringside, shouted, "This could be the upset of the century!" Mort Sharnik described the moment: "Cassius hit Liston with a one-two combination; a jab followed by a straight right. Cassius pulled the jab back and there was a mouse underneath Sonny's right eye. Then he pulled the right back and there was a gash underneath the other eye. ... It was like the armor plate of a battleship being pierced. I said to myself, 'My God, Cassius Clay is winning this fight!'" A clearly angered Liston rallied at the end of the round, as Clay seemed tired, and delivered punishing shots to Clay's body. It was probably Liston's best moment in the entire fight. But as the round ended, Clay shouted to him, "you big sucka, I got you now". Sitting on his stool between rounds, Liston was breathing heavily as his cornermen worked on his cut.

During the fourth round, Clay coasted, keeping his distance and Liston appeared dominant. Joe Louis commenting on TV at ringside said "It's looking good for Sonny Liston". However, when Clay returned to his corner, he started complaining that there was something burning in his eyes and he could not see. "I didn't know what the heck was going on," Angelo Dundee, Clay's trainer, recalled on an NBC special 25 years later. "He said, 'cut the gloves off. I want to prove to the world there's dirty work afoot.' And I said, 'whoa, whoa, back up baby. C'mon now, this is for the title, this is the big apple. What are you doing? Sit down!' So I get him down, I get the sponge and I pour the water into his eyes trying to cleanse whatever's there, but before I did that I put my pinkie in his eye and I put it into my eye. It burned like hell. There was something caustic in both eyes."

The commotion wasn't lost on referee Barney Felix, who was walking toward Clay's corner. Felix said Clay was seconds from being disqualified. The challenger, his arms held high in surrender, was demanding that the fight be stopped and Dundee, fearing the fight might indeed be halted, gave his charge a one-word order: "Run!"

Clay later said he could only see a faint shadow of Liston during most of the round, but by circling and moving he managed to avoid Liston and somehow survive. By the sixth round, Clay's sight had cleared, and he began landing combinations almost at will. "I got back to my stool at the end of the sixth round, and under me I could hear the press like they had gone wild," Clay later said. "I twisted round and hollered down at the reporters, 'I'm gonna upset the world.'"

There are two basic narratives about what occurred next in Liston's corner. According to Ali biographer David Remnick, Liston told his cornermen, "That's it." This supposedly rallied Liston's handlers, who thought he meant he was finally angry enough to win, but Liston really meant that he was through fighting, which he indicated by spitting out his mouth guard.

However, Liston biographer Paul Gallender's take is that Liston's shoulder was essentially paralyzed by the end of round six, and his corner made the decision to end the fight, despite Liston's protests. Liston spit out his mouth guard in disgust, still not believing that Clay was the superior fighter.

As the bell sounded for the seventh round, Clay was the first to notice that Liston had spat out his mouth guard. Clay moved to the middle of the ring with his arms raised, dancing the jig that would become known as the "Ali Shuffle" while Howard Cosell, broadcasting at ringside, shouted "wait a minute! Wait a minute! Sonny Liston is not coming out!" Liston failed to answer the bell for the seventh round, and Clay was declared the winner by technical knockout. Liston became the first World Champion since Jess Willard in 1919 to retire on his stool during a Heavyweight title fight. At that point the bout was level on the official scorecards of the referee and two judges.

Sensing that he had made history, Clay quickly ran to the ropes amidst the commotion in the ring and shouted at sportswriters, "Eat your words!" In a scene that has been rebroadcast countless times over the ensuing decades, Clay repeatedly yelled "I'm the greatest!" and "I shook up the world."

Clay had to be persuaded to hold the traditional post-fight press conference. He called the writers "hypocrites" and said, "Look at me. Not a mark on me. I could never be an underdog. I am too great. Hail the champion!"

On February 27, 1964, Clay announced that he was a member of the Nation of Islam. His membership in the group was first disclosed the previous night at the group's annual national convention in Chicago by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad.

"I began worshiping this way five years ago when I heard a fellow named Elijah Muhammad on the radio talking about the virtues of the Islam religion," Clay said. "I also listened to his ministers. No one could prove him or them wrong, so I decided to join."

Clay started going by the name Cassius X, as members of the organization adopt the last name X because they no longer want to bear names handed down by former slave-owning families.

On March 1, 1964, Ed Sullivan said on his show: "I saw the Liston-Clay fight. This was a stinker of all-time. I swear The Beatles could beat the two of 'em! No kidding!" The Beatles had been on The Ed Sullivan Show twice in February. During their second appearance, which aired February 16 from Miami, Sullivan actually had Liston and Joe Louis—who were in the audience—stand up for applause; the group also visited Clay's training center later in the week.

On March 6, 1964, Elijah Muhammad announced in a recorded statement played over the radio that Clay would be renamed Muhammad Ali. Muhammad means "worthy of all praises", and Ali means "most high".

Did Liston's corner deliberately blind Clay?

Many theorized that a substance used on Liston's cuts by Joe Pollino, his cutman, may have inadvertently caused the irritation that blinded Clay in round four. "Joe Pollino had used Monsel's Solution on that cut," Angelo Dundee said. "Now what had happened was that probably the kid put his forehead leaning in on the guy—because Liston was starting to wear in with those body shots—and my kid, sweating profusely, it went into both eyes."

Two days after the fight, heavyweight contender Eddie Machen said he believed that Liston's handlers made deliberate use of illegal medication to temporarily blind Clay. "The same thing happened to me when I fought Liston in 1960," Machen said. "I thought my eyes would burn out of my head, and Liston seemed to know it would happen." He theorized that Liston's handlers would rub medication on his shoulders, which would then be transferred to his opponent's forehead during clinches and drip into the eyes. "Clay did the worst thing when he started screaming and let Liston know it had worked," Machen said. "Clay panicked. I didn't do that. I'm more of a seasoned pro, and I hid it from Liston." It is noteworthy that Machen did not mention the eye burning problem immediately after his fight with Liston, citing an injury to his arm as contributing to his defeat.

Shoulder injury

Liston said he quit the fight because of a shoulder injury, and there has been speculation since about whether the injury was severe enough to actually prevent him from continuing. Immediately after the fight, Liston told broadcasters that he hurt the shoulder in the first round. Dr. Alexander Robbins, chief physician for the Miami Beach Boxing Commission, diagnosed Liston with a torn tendon in his left shoulder.

For his book, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, David Remnick spoke with one of Liston's cornermen, who told him that Liston could have continued: " was all BS. We had no return bout clause with Clay, and if you say your guy just quit, who is gonna get a return bout. We cooked up that shoulder thing on the spot."

Sports Illustrated writer Tex Maule wrote that Liston's shoulder injury was legitimate. He cited Liston's inability to lift his arm: "There is no doubt that Liston's arm was damaged. In the sixth round, he carried it at belt level so that it was of no help in warding off the right crosses with which Clay probed at the cut under his left eye." He also cited medical evidence: "A team of eight doctors inspected Liston's arm at St. Francis Hospital in Miami Beach and agreed that it was too badly damaged for Liston to continue fighting. The torn tendon had bled down into the mass of the biceps, swelling and numbing the arm."

Those findings were confirmed in a formal investigation immediately after the fight by Florida State Attorney Richard Gerstein, who also noted that there was little doubt that Liston went into the fight with a sore or lame shoulder. Despite Liston carrying an injury and being undertrained, Ali stated in 1975 that this fight was his toughest ever.

Allegations of a fix

There were allegations of a fix as soon as the fight ended. Arthur Daley of the New York Times did not believe the claim. He wrote:

When a fight ends in the fashion this one did, with the unbeatable monster remaining in his corner, suspicions of larceny are immediately aroused. They are not helped by the fact that Liston, an ex-convict, was sponsored by mobsters at the start of his career. For the larceny theory to be valid, however, there would have to be an overwhelming reason for it. The prospects of a betting coup can be dismissed because the 8-to-1 odds in Liston's favor never varied more than a point. If there had been a rush of smart money on the underdog, the odds would have plummeted. This is an unfailing barometer of hanky-panky. What would Liston have gained by throwing the fight? The heavyweight championship is the most valuable commodity in the world of sports and not even a man of Liston's criminal background would willingly toss it away. It also brought him an aura of respectability such as he never had known before.

After a month-long investigation, Florida State Attorney Richard E. Gerstein said there was no evidence to support the claim of a fix, and a United States Senate subcommittee conducted hearings three months later and also found no evidence of a fix.

Documents were released to the Washington Times in 2014 under the Freedom of Information Act which show the FBI suspected the fight may have been fixed by Ash Resnick, a Las Vegas figure tied to organized crime and to Liston. The documents show no evidence that Ali was in on the scheme or even knew about it, and nothing suggests the bureau ever corroborated the suspicions it investigated. The memos were addressed directly to Director J. Edgar Hoover.

A memo dated May 24, 1966, which the Washington Times called "the most tantalizing evidence," details an interview with a Houston gambler named Barnett Magids, who described to agents his discussions with Resnick before the first Clay-Liston fight. The Washington Times reported:

"On one occasion, Resnick introduced Magids to Sonny Liston at the Thunderbird, ," the memo states. "About a week before the Liston and Clay fight in Miami, Resnick called and invited Magids and his wife for two weeks in Florida on Resnick. Magids' wife was not interested in going, but Magids decided to go along, and Resnick was going to send him a ticket.

"Two or three days before the fight, Magids called Resnick at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami to say he could not come," the memo states. "On this call, he asked Resnick who he liked in the fight, and Resnick said that Liston would knock Clay out in the second round. Resnick suggested he wait until just before the fight to place any bets because the odds may come down.

"At about noon on the day of the fight, reached Resnick again by phone, and at this time, Resnick said for him to not make any bets, but just go watch the fight on pay TV and he would know why and that he could not talk further at that time.

"Magids did go see the fight on TV and immediately realized that Resnick knew that Liston was going to lose," the document states. "A week later, there was an article in Sports Illustrated writing up Resnick as a big loser because of his backing of Liston. Later people 'in the know' in Las Vegas told Magids that Resnick and Liston both reportedly made over $1 million betting against Liston on the fight and that the magazine article was a cover for this."

The article was controversial, with Ron Kantowski of the Las Vegas Review-Journal writing that the Washington Times article "had more holes than the left side of the Cubs' infield." He continued:

Here, then, is the most titillating part of the Washington Times story: "At about noon on the day of the fight, (Barnett Magids) reached Resnick again by phone, and at this time, Resnick said for him to not make any bets, but just go watch the fight on pay TV, and he would know why ..."

This was after the weigh-in, when Ali went berserk and Sonny just burped up a couple of ... hot dogs.

Is it possible this is why Ash Resnick might have told Barnett Magids—according to Magids—not to make any bets on Liston?

According to a Sports Illustrated story, Resnick lost a lot of money betting on Liston. ... The Washington Times' story suggested ... the magazine story may have been a cover-up, quoting "people in the know."

Sometimes in boxing, a guy trains on hot dogs and beer, and then maybe he injures his shoulder. A guy everybody expects to win, doesn't win. And then there are FBI files and conspiracy theories, and then "people in the know" want to put a guy like Sonny Liston on the grassy knoll with a smoking gun in his hand.

Reports

Result List

Result Description

Clay, who was a 8–1 underdog, won in a major upset, when the champion gave up at the opening of the seventh round

Popular Tweets

Fanart

Banner

User Comments

No comments yet..

No comments yet..

Other Event Name![]()

Potential Filename

Download Metadata