Event

Cassius Clay vs Sonny Liston

Date

Tue 25th May 1965 (UTC)

Tue 25th May 1965 (Local)

Timestamp

1965-05-25T00:00:00

Time

00:00:00 UTC

00:00:00 UTC

Poster

Your Rating (Click a star below)

Cassius Clay vs Sonny Liston

Date

Tue 25th May 1965 (UTC)

Tue 25th May 1965 (Local)

Timestamp

1965-05-25T00:00:00

Time

Poster

Your Rating (Click a star below)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Total Rating![]() (0 users)

(0 users)

Thumb

Square Poster

League

Boxing

Season

1965

Round

0

Status

Location Civic Cente

Civic Cente

Video Highlights

Description

Background

Following Clay's upset victory over Liston, both fighters were almost immediately embroiled in controversy that was considered detrimental to the sport of boxing. A couple of days after the fight, Clay publicly announced that he had joined the "Black Muslims"—which at the time was widely viewed as a hate group against white people—and started going by the name Cassius X. The following month, he was renamed Muhammad Ali by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. This evoked widespread public condemnation. Martin Luther King Jr. said, "When Cassius Clay joined the Black Muslims and started calling himself Cassius X, he became a champion of racial segregation." As for Liston, he was arrested on March 12 and charged with speeding, careless and reckless driving, driving without an operator's license and carrying a concealed weapon. The arresting officer said the former champion was driving between 76 and 80 mph (122–129 km/h) in a residential zone. Liston had a loaded .22 caliber revolver in his coat pocket and there were empty bottles of vodka in the car. A young woman was in the car with Liston, but she was not arrested. In short, at a time when Congress was investigating corruption and organized crime influence in boxing, neither fighter was seen as a poster child for the sport.

In the view of some, the unexpected ending of the bout took on suspicious overtones when it was discovered that the two fighters had a contract which contained a rematch clause. Many argued that Liston had more to gain financially from losing the bout and fighting a rematch than he did from winning. The contract gave Inter-Continental Promotions, Inc., a firm organized to promote Liston's fights, the right to promote Ali's first fight as champion—if he should beat Liston—and pick his opponent (Liston, of course). This was in a second contract, kept secret and not part of the main fight contract. It was phrased as it was because the World Boxing Association did not allow fight contracts with rematch clauses. Gordon B. Davidson, an attorney for the group sponsoring Ali, said, "We felt we would be better advised not to have a guaranteed rematch clause. We felt this was more in the spirit of the WBA rules than a direct rematch which was clearly outlawed." He agreed that it was "subterfuge." When Ali and Liston signed to fight a rematch, the WBA voted unanimously to strip Ali of the title and drop Liston from its rankings. However, the World Boxing Council, the New York State Athletic Commission and The Ring magazine continued to recognize Ali as champion.

Pressed by the WBA—which included every U.S. state except California, Nevada and New York—state boxing commissions throughout the nation were reluctant to license a rematch between the two controversial fighters, and it was difficult to find a venue. Ultimately, Massachusetts agreed to host the bout, which resulted in the suspension of the Massachusetts Boxing Commission by the WBA. The fight was set for November 16, 1964, at the Boston Garden. Liston was immediately established as a 13-5 favorite, making Ali a greater betting underdog than Floyd Patterson in his two fights against Liston. This time, Liston trained hard, preparing himself for a 15-round bout. In fact, Time magazine said that Liston had worked himself into the best shape of his career. Ali, for his part, continued to taunt Liston, dragging a bear trap to the pre-fight physical and announcing that he might begin manufacturing the "Sonny Liston Sit-Down Stool." However, the Boston fight would never occur. Three days before the scheduled bout (on a Friday the 13th, as it were), Ali needed emergency surgery for a strangulated hernia. The bout would need to be delayed by six months.

The new date was set for May 25, 1965. But as it approached, Liston was involved in yet another arrest and there were fears that the promoters were tied to organized crime. Massachusetts officials, most notably Suffolk County District Attorney Garrett H. Byrne, began to have second thoughts. Byrne sought an injunction blocking the fight in Boston because Inter-Continental Promotions was promoting the fight without a Massachusetts license. Inter-Continental said local veteran Sam Silverman was the promoter. On May 7, backers of the rematch ended the court battle by pulling the fight out of Boston.

Lewiston, Maine

The Androscoggin Bank Colisée, in Lewiston, Maine

The promoters needed a new location quickly, whatever the size, to rescue their closed circuit television commitment around the country. Governor John H. Reed of Maine stepped forward, and within a few hours, the promoters had a new site: Lewiston, Maine, a mill town with a population of about 41,000 located 140 miles (230 km) north of Boston. Inter-Continental obtained a permit and made an arrangement to work with local promoter Sam Michael. The venue selected was the Central Maine Youth Center (now called Androscoggin Bank Colisée), a junior hockey rink. Lewiston was the smallest city to host a heavyweight title bout since Jack Dempsey fought Tom Gibbons in Shelby, Montana (population 3,000) in 1923. It remains the only heavyweight title fight held in the state of Maine.

The fight was embraced by the Pine Tree State. Governor Reed announced to the press, "This is one of the greatest things to happen in Maine." Nevertheless, it would go down in history as a debacle.

The atmosphere surrounding the fight was tense and sometimes ugly, largely due to the repercussions of Ali's public embrace of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X, who had a public and bitter falling out with Elijah Muhammad, had been assassinated several months before the fight, and the men arrested for the slaying were members of the Nation of Islam. Rumors circulated that Ali, who had publicly snubbed Malcolm after his break with Elijah Muhammad, might be killed by Malcolm's supporters in retaliation. The FBI took the threats seriously enough to post a 12-man, 24-hour guard around Ali. Liston's camp, in turn, claimed he had received a death threat from the Nation of Islam. The Fruit of Islam—the omnipresent, bow-tied paramilitary wing of the Nation of Islam—surrounding Ali only added to the sense of foreboding and hostility. Security for the fight was unprecedented.

The phantom/anchor punch

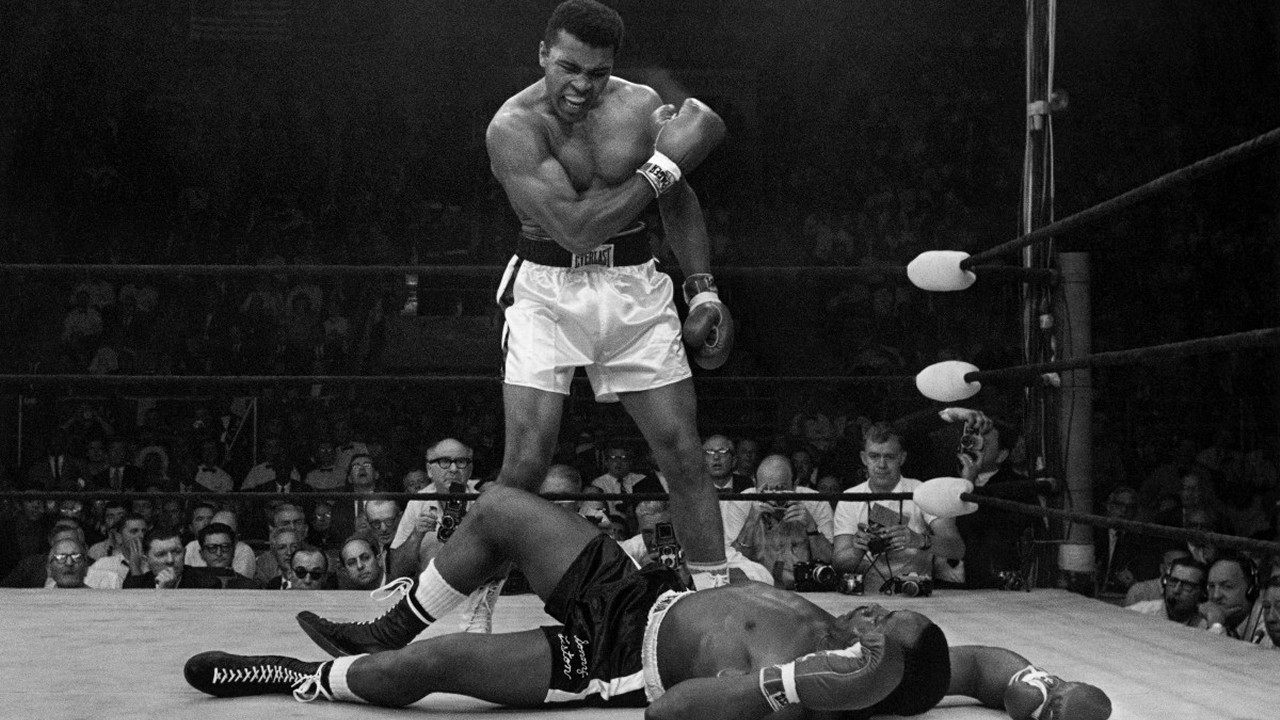

The ending of the second Ali-Liston fight remains one of the most controversial in boxing history. Midway through the first round, Liston threw a left jab and Ali supposedly went over it with a fast right, knocking the former champion down. Liston went down on his back. He rolled over, got to his right knee and then fell on his back again. Many in attendance did not see Ali deliver the punch. The fight quickly descended into disarray. Referee Jersey Joe Walcott, a former World Heavyweight Champion himself, had a hard time getting Ali to go to a neutral corner. Ali initially stood over his fallen opponent, gesturing and yelling at him, "Get up and fight, sucker!" and "Nobody will believe this!" The moment was captured by ringside photographer Neil Leifer in what became one of the most iconic images in sport, chosen as the cover of the Sports Illustrated special issue, "The Century's Greatest Sports Photos." Ali then began prancing around the ring with his arms raised in victory.

When Walcott got back to Liston and looked at the knockdown timekeeper, Francis McDonough, to pick up the count, Liston had fallen back on the canvas. Walcott never did pick up the count. He said he could not hear McDonough, who did not have a microphone. Also, McDonough did not bang on the canvas or motion a number count with his fingers. McDonough, however, claimed Walcott was looking at the crowd and never at him. After Liston arose, Walcott wiped off his gloves. He then left the fighters to go over to McDonough. "The timekeeper was waving both hands and saying, 'I counted him out—the fight is over,'" Walcott said after the fight. "Nat Fleischer was seated beside McDonough and he was waving his hands, too, saying it was over." Walcott then rushed back to the fighters, who had resumed boxing, and stopped the fight—awarding Ali a first-round knockout victory.

It is one of the quickest heavyweight title knockouts in history. Many in the small crowd had not even settled in their seats when the fight was stopped. The official time of the stoppage was announced as 1:00 into the first round, which was wrong. Liston went down at 1:44, got up at 1:56, and Walcott stopped the fight at 2:12.

McDonough and Fleischer were also wrong in their interpretation of how the rules applied. Under the rules, the timekeeper is supposed to start the count at the time of a knockdown. The referee's duty is to get the boxer scoring the knockdown to a neutral corner, pick up the count from the timekeeper and continue it aloud for the knocked down boxer. Under the rules of the Maine Commission, the referee was authorized to stop his count if a boxer refused to go to the proper corner. "It might have been better if Walcott had stopped the count (by the knockdown timekeeper) until Clay went to the neutral corner and then started again," said Duncan MacDonald, a commission member.

"I did my job," Walcott said. "He looked like a man in a different world. I didn't know what he might do. I thought he might stomp him or pick him up and belt him again."

"If that bum Clay had gone to a neutral corner instead of running around like a maniac, all the trouble would have been avoided," McDonough said. He acknowledged that Walcott could have asked him to start the count again "after he got that wild man—Clay—back to a neutral corner, but he didn't, so that was that."

Alleged match fixing

When the fight ended, numerous fans booed and started yelling, "Fix!" Skeptics called the knockout blow "the phantom punch." Ali called it "the anchor punch." He said it was taught to him by comedian and film actor Stepin Fetchit, who learned it from Jack Johnson. However, Ali was unsure immediately after the fight as to whether or not the punch connected, as footage from the event shows Ali in the ring asking his entourage, "Did I hit him?" Ali told Nation of Islam minister Abdul Rahman that Liston "laid down" and Rahman replied, "No, you hit him." Rahman later said, "Ali hit him so fast, Ali didn't really know he hit him. ... and It took a long time before even he saw the punch he hit Sonny with." Tellingly, Ali never threw the 'anchor punch' again nor did he subsequently refer to it.

After the fight, George Chuvalo climbed through the ropes and shoved Ali, yelling, "Fix!" He was restrained, but later he said that he had seen Liston's eyes while the challenger was on the floor, and he knew that he was not in bad shape. "His eyes were darting from side to side like this," he said, darting his eyes from side to side. "When a fighter is hurt his eyes roll up."

There were some at ringside who believed the fight was legitimate. Larry Merchant, who was a critic of Liston as a person throughout his career, wrote 50 years later, "I saw the actual punch land on the actual chin, as did others in my area of the press section. It was a quick right hand that caught Liston as he was coming forward ... According to ringside doctors I've spoken to, that is a classic example of a medulla oblongata K.O." World Light Heavyweight Champion José Torres said, "It was a perfect punch." Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wrote that it was "no phantom punch." Tex Maule of Sports Illustrated wrote, "The blow had so much force it lifted Liston's left foot, upon which most of his weight was resting, well off the canvas."

"Many people in the arena did not see , understandably", Merchant wrote: "Or they couldn't believe that it had the force to knock out the seemingly indestructible former champion". He described the belief that the fight was rigged as "the apparently unkillable myth ... many people believe that the moon landings were staged, probably right there in Lewiston". Slow motion examination of the fight recording shows that the 'punch' that landed was a short grazing right to Liston's cheek and of apparently limited power. Hall of Fame announcer Don Dunphy was one of many who didn't believe the fight was on the level. "If that was a punch, I'll eat it," he said. "Here was a guy who was in prison and the guards to beat him over the head with clubs and couldn't knock him down." But others contend that he wasn't the same Liston. Dave Anderson of the New York Times said Liston "looked awful" in his last workout before the fight. Liston's handlers secretly paid sparring partner Amos Lincoln an extra $100 to take it easy on him. Arthur Daley of the New York Times wrote that Liston's handlers knew he "didn't have it anymore." These statements don't accord with the fact that three years later Liston easily knocked out Lincoln within two rounds.

One ringside observer, former World Heavyweight Champion James J. Braddock, said the suspect Ali right hand merely finished up what an earlier punch had begun. "I have a feeling that this guy (Ali) is a lot better than any of us gave him credit for," Braddock said. "It isn't the knockout punch that sticks in my mind as much as a punch he let go (earlier). ... It was a right to Liston's jaw and it shook him to his shoetops. For all we know, it could have been the one that set up the knockout."

Another former champion, Rocky Marciano, changed his view about the knockout punch after seeing videotape the next day. "I didn't think it was a powerful punch when I saw the fight from ringside," Marciano said. "Now (after seeing video) I think Clay, seeing the opening, snapped the punch the last six inches." He added that he still didn't think it was a knockout punch.

Ali did not think he knocked Liston out. In his own words in Thomas Hauser's 1991 biography: "The punch jarred him. It was a good punch, but I didn't think I hit him so hard that he couldn't have gotten up. Once he went down, I got excited. I forgot about the rules". In that same book, Liston, quoted two years after the fight: "Ali knocked me down with a sharp punch. I was down but not hurt, but I looked up and saw Ali standing over me. ... Ali is waiting to hit me, the ref can't control him".

Dave Anderson said he saw Liston in Las Vegas in 1967 and asked him what happened. "It wasn't that hard a punch, but it partially caught me off balance and when I got knocked down, I got mixed up because the referee never gave me a count," Liston said. "I was listening for a count. That's the first thing you do, but I never heard a count because Clay never went to a neutral corner."

Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star-Ledger said Liston told him that he lost simply because "the timekeeper couldn't count."

Mark Kram of Sports Illustrated said Liston told him: "That guy was crazy. I didn't want anything to do with him. And the Muslims were coming up. Who needed that? So I went down. I wasn't hit."

Wilfred Sheed offered his opinion in his 1975 book, Muhammad Ali: A Portrait in Words and Photographs, writing that Liston was going to throw the fight going in and, when he suffered a legitimate flash knockdown in round one, decided on the spot to seize the opportunity and end the fight. It was Walcott's confusion and Ali's behavior that forced Liston to feign disorientation for far longer than a knockdown of that type would have caused.

During a 1995 HBO documentary about Liston, Johnny Tocco, who owned a boxing gym in Las Vegas, said he spoke with mobster John Vitale before the rematch and was told not to pay any attention to what he heard about the fight. He also told Tocco that he should be glad that he wasn't going to Lewiston. When Tocco asked why, Vitale told him that the fight was going to end in the first round.

During the same documentary, former FBI agent William F. Roemer Jr. said, "We learned that there very definitely had been a fix in that fight." He said Bernie Glickman, a boxing manager from Chicago with mob ties, claimed that while he was conversing with Liston and his wife before the fight, Liston's wife told the ex-champion that as long as he had to lose the fight, he should go down early to avoid any chance of getting hurt.

In the wake of the controversial fight, there was an outcry by press and politicians for the abolition of boxing. Bills to ban the sport were planned in several state legislatures.

A promoter in San Antonio apologized to his theater TV customers and, on the basis that they had been defrauded by a "shameful spectacle," donated his take to boys' clubs. The California legislature, in session, received a resolution calling for an investigation by the state attorney general to determine if its closed-circuit viewers had been fraudulently duped out of their money.

For those who believe that Liston took a dive, there are a number of theories as to why, including: (1) The Mafia forced Liston to throw the fight as part of a betting coup. (2) Liston bet against himself and took a dive because he owed money to the Mafia. (3) A couple of members of the Nation of Islam visited Liston's training camp and told Liston they would kill him if he won the rematch. (4) Author Paul Gallender claims that members of the Nation of Islam kidnapped Liston's wife, Geraldine, and Liston's son, Bobby. Liston was told to lose the fight to Ali or he would never see his family again. (5) Liston was afraid that he would be accidentally shot by followers of Malcolm X as they tried to kill Ali in the ring. There were also claims attributed to Liston and others that he threw the fight in return for a share of the more marketable Ali's future purses. Credence to these claims is provided by the fact that after his last fight, with Chuck Wepner, Liston seemed more preoccupied in supporting the proposed Ali-Frazier bout and Ali's claims to the title than about his own career.

In the final analysis, it remains inconclusive whether the blow in Lewiston was a genuine knockout punch. The fact that Liston didn't complain about the clear breach of boxing rules (being declared knocked out without a count) and Ali's obvious state of bewilderment, shouting at Liston "Nobody will believe this" and asking his handlers "Did I hit him?" confirmed most people's belief that Liston took a dive.

Reports

Result List

|  |  | WIN | ||

Result Description

Ali won with a first-round knockout.

Popular Tweets

Fanart

Banner

User Comments

No comments yet..

No comments yet..

Other Event Name![]()

Potential Filename

Download Metadata